Understanding Card Payments as a Product Manager

The Story of modern card payments began not with technology, but with an awkward dinner. In 1950, Frank McNamara sat at a New York restaurant and realised he had left his wallet at home. Forced to promise repayment later, that embarrassment birthed an idea. A year later, he returned with the Diners Club Card: a cardboard charge card that could be used at multiple restaurants.

The idea was simple: instead of carrying cash or opening tabs at individual restaurants, diners could use one universal card to pay, and then settle the bill later with Diners Club. For restaurants, it meant attracting more customers without having to manage the risk of lending directly. For cardholders, it meant convenience and flexibility.

That model unlocked a powerful network effect: the more restaurants that accepted the card, the more valuable it became for customers; and the more customers carried it, the harder it became for restaurants not to accept it. What started as a niche dining card soon spread into travel, retail, and beyond laying the foundation for bank-issued cards, the rise of global card schemes and today’s global, digital-first payment ecosystem.

Decades later; swiping, tapping, or entering card details online feels effortless. Yet behind those seconds of convenience lies a sophisticated choreography between key stakeholders and systems.

Last week, I shared an article breaking down payment processing as a whole. That’s a great starting point if you want the full picture. But now, we’re zooming in an important piece of that puzzle: Card payments.

In this article, we’ll cover:

What Card payments are and the different types available

Major Card schemes/Networks

Key Players involved in Card Transactions

The Processing flow for Card Transactions and

Factors to Consider Before Issuing Cards to Customers as a Product Offering

By the end, you’ll understand not just how cards “work,” but why mastering their mechanics is critical for product managers looking to create seamless, trusted, and revenue optimised payment experiences.

Fair warning, this is a detailed article. But if you stick with it, you’ll walk away with a complete understanding of card payments and be glad you did.

Comfortable? Alright let’s dive in.

First, let's start with the basics : what exactly is a card?

A Card is a physical or digital instrument issued by a bank or financial institution that allows its holder to pay for goods and services without using cash. It acts as a secure link between the customer’s account and the merchant, enabling money to move through established networks in a standardised way. Today, cards exist in many forms but they all share the same purpose: to provide a simple, trusted way to pay.

Of course, to serve this purpose, a card is more than just plastic with a number on it. Every detail printed, embedded, or encoded onto it has a role in making payments possible and secure. This brings us to examining the anatomy of a card, to help understand what’s on a card and why it matters.

Here are what the key parts mean:

MII (Major Industry Identifier): This is the very first digit of the card number. It tells you which industry issued the card. For example, numbers starting with 4 or 5 usually mean banking/payment services ( for Visa, Mastercard).

IIN/BIN (Issuer Identification Number / Bank Identification Number): The first 6–8 digits of the card number. These identify the financial institution that issued the card. Think of it as the "address" that tells the payment network which bank to contact.

Note: With more card issuers in the world, BINs are being expanded from 6 to 8 digits to avoid running out of numbers.

Account Identifier: This is middle section of the card number. It is unique to the individual cardholder’s account. It’s like your "seat number" within the bank’s system.

Checksum (Last Digit): This is the final digit of the card number, calculated using the Luhn algorithm. It’s a security check to quickly spot errors or invalid numbers.

Expiration Date: This tells when the card will stop working. It’s a control measure for card replacement and fraud prevention.

CVV (Card Verification Value): A 3–4 digit code printed on the back of the card, not stored on the magnetic stripe or chip. This helps confirm the card is physically present when making online or card-not-present purchases.

Cardholder’s Name: The person authorized to use the card. This doesn’t always mean they opened the account, they might just be an authorised user.

EMV Chip: This is the small metallic square. Unlike the old magnetic stripe, the chip generates a unique transaction code each time it’s used, making it far harder to clone

Types of Cards

Now that we’ve broken down the physical features of a card, the next natural question is: are all cards the same?

The answer is no. While the anatomy of a card looks very similar across the board, the purpose of the card, who pays, and how the funds move can differ widely. Here are the key types you should know.

Credit cards - these allow the cardholder to borrow funds from the issuing bank up to a set limit, with the option to repay later typically incurring interest if the balance isn’t paid in full. In these transactions, the issuer pays the merchant at the point of sale, and the cardholder owes the issuer. Credit cards are popular for everyday spending, large purchases, and travel, often offering loyalty rewards. They generally carry higher interchange fees for merchants but come with strong fraud protection and can be integrated into loyalty or rewards systems.

Debit cards - these are linked directly to a cardholder’s bank account, with payments deducted almost immediately after the transaction. The system authorises transactions in real-time against available funds. Debit cards are widely used for day-to-day spending and ATM withdrawals. They tend to have lower interchange fees than credit cards and faster settlement times, but they also face higher decline rates if there are insufficient funds.

Prepaid cards are loaded with a fixed amount before use and can only be used up to the available balance. They work like debit cards but are not linked to a traditional bank account. Prepaid cards are common as gift cards, travel cards, corporate expense cards, and tools for financial inclusion. For PMs, they’re useful for controlled spending scenarios, have low overdraft risk, and can be tailored to niche segments such as unbanked customers.

Virtual cards are digital-only versions of cards with unique card numbers, CVVs, and expiration dates. They are typically issued instantly via an app and work on the same networks as physical cards, but they are intended for card-not-present transactions like online or in-app purchases. Virtual cards are ideal for secure online shopping, subscriptions, and temporary usage to reduce fraud exposure. They can be issued at scale via APIs, making them particularly attractive for embedded finance products.

Card schemes

No matter the type of card you own, one thing is constant: a card cannot function on its own.

Think of it like this:

A card is a car — it has a design (the anatomy), different models (types of cards), and an owner (the cardholder).

But even the best car is useless without roads and highways to connect it to other places.

That’s where card schemes come in.

A card scheme is essentially the payment network that provides those “roads.” It connects the issuing banks (the banks that provide cards to customers) with acquiring banks (the banks that process transactions for merchants), ensuring money and data flow securely between them.

What Card Schemes Do

Card schemes perform several critical functions:

Set standards: Define the operational and technical rules for transactions (e.g., EMV chip standards, encryption, security protocols).

Govern economics: Establish interchange fees, chargeback processes, and dispute resolution rules.

Provide infrastructure: Offer the global or regional network through which transaction data travels.

Ensure interoperability: Make it possible for a card issued by one bank to work at a merchant serviced by another bank or processor.

Without card schemes, your card would only work at merchants directly connected to your bank; meaning no cross-bank, cross-border, or even cross-city payments. Schemes make cards universally usable within their networks.

Major Card Schemes in Existence

Card schemes come in two broad categories: global networks that enable worldwide acceptance, and domestic networks designed to meet local market needs.

1. Global Card Schemes

These are the “international highways” of card payments, connecting banks, merchants, and customers across countries and continents.

Some Major examples are:

Visa: The largest global network. Visa doesn’t issue cards itself; instead, it partners with banks and processors. Known for near-universal acceptance, reliability, and strong fraud-prevention measures.

Mastercard: A close rival to Visa, powering debit, credit, prepaid, and contactless cards. Mastercard is widely accepted across the globe and continually invests in payment innovation.

American Express (Amex): Unlike Visa and Mastercard, Amex often acts as both issuer and network. Known for premium services, strong rewards programs, and higher merchant fees, which sometimes limit acceptance compared to Visa/Mastercard.

Discover: A U.S.-based network with international reach through partnerships (e.g., Diners Club). Like Amex, Discover may also serve as both network and issuer.

UnionPay: The dominant card scheme in China, with the largest number of cards issued globally. UnionPay has expanded internationally, partnering with merchants and networks across Asia, Africa, and beyond.

2. Domestic Card Schemes

These are “local highways” created by governments or regulators to reduce dependence on foreign schemes, lower transaction costs, and support financial inclusion.

While they often begin with a focus on serving their home market, some have expanded beyond borders through global partnerships, eventually achieving international reach. For example, Nigeria’s Verve card, once a purely domestic brand, has extended its acceptance footprint across Africa and into global markets.

Some Major examples are:

Verve – Nigeria’s domestic scheme, dominant in local acceptance and integrated into Interswitch’s payment ecosystem.

Afrigo – Nigeria’s national domestic card scheme launched in 2023 by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) in collaboration with the Nigeria Inter-Bank Settlement System (NIBSS).

RuPay – India’s domestic scheme by NPCI, aimed at financial inclusion and cost-effective transactions.

Elo – Brazil’s local card brand created by three major Brazilian banks.

Troy – Turkey’s national card scheme supporting domestic payments and e-commerce.

Mir – Russia’s domestic scheme developed to ensure payment independence.

The Key players involved in Card Transactions

When people talk about the “key players” in card transactions, they usually refer to the three- or four-party model which includes the Cardholder, Merchant, Issuer (the cardholder’s bank) and Acquirer (the merchant’s bank).

This simplified model is useful for high-level explanations, but it leaves out several other critical actors. To give you a fuller picture and, as a PM, to help you understand the factors that truly determine success and transaction quality; I’ve expanded the list to include players like payment gateways, processors, terminal management systems and fraud systems.

1. The Cardholder

This is the customer; the individual or business that owns and uses the card. The cardholder initiates a payment by either swiping/tapping their card in-store, or entering their card details online. Their role may seem passive, but they are the starting point of every transaction. Without them, no payment journey begins.

2. The Merchant

The business or service provider that accepts card payments for their goods or services. Merchants can be brick-and-mortar stores (using POS terminals) or online platforms (accepting payments via websites or apps). They depend on acquirers and gateways to receive the funds securely, while also balancing customer experience (fast, smooth checkout) with security.

3. The Payment Gateway

A payment gateway acts as the digital cashier for online or in-app transactions. It securely captures sensitive card details (like card number, CVV, expiry date), encrypts them, and transmits this data to the acquirer or processor. Gateways also screen for fraud and ensure compliance with security standards like PCI DSS.

4. The Acquirer (Acquiring Bank)

The acquirer is the merchant’s bank or financial partner. They take the transaction information from the gateway (online) or POS terminal (offline), and pass it into the card network. They also settle funds back into the merchant’s account once the issuer approves.

5. The Issuer (Issuing Bank)

The issuer is the cardholder’s bank — the institution that provides the customer with their debit, credit, or prepaid card. The issuer’s critical role is to decide whether a transaction should be approved or declined. It checks for available funds (for debit/prepaid) or credit limits (for credit cards), validates security credentials (PIN, CVV, OTP), and applies fraud checks. Essentially, the issuer is the gatekeeper of the customer’s money.

6. The Card Network (Scheme)

Aka Schemes, these are the “roads” that connect issuers and acquirers. Card networks like Visa, Mastercard, Amex etc define the rules, standards, and technology that make transactions possible. They securely route the authorisation requests from the acquirer to the issuer and send the response back. Without schemes, a card would only work at merchants connected to the same bank that issued it.

7. Payment Processors

Processors are the plumbing of the card payments ecosystem. They don’t usually interact directly with customers, but they make sure payment data flows smoothly between merchants, gateways, acquirers, networks, and issuers. Some processors are large, independent players (like Fiserv, Worldpay), while in other cases, the acquirer itself provides processing services. They ensure speed, accuracy, and uptime for millions of transactions every second.

8. Terminal Management Systems(TMS)

A TMS allows acquirers or service providers to remotely manage fleets of POS devices pushing software updates, applying new security protocols, configuring parameters, or even remotely disabling a terminal if it’s compromised. TMS keeps the devices merchants use to accept payments running smoothly, securely, and in compliance with global standards.

9. Fraud & Risk Systems

Every transaction is checked in real time by fraud and risk management systems. These systems look for suspicious behaviour ; for example, a card being used in Lagos and then in London 5 minutes later, or an unusually large purchase that doesn’t match the cardholder’s history. They use machine learning models, rules engines, and real-time monitoring to block fraud before it happens. This layer is critical for protecting both consumers and merchants.

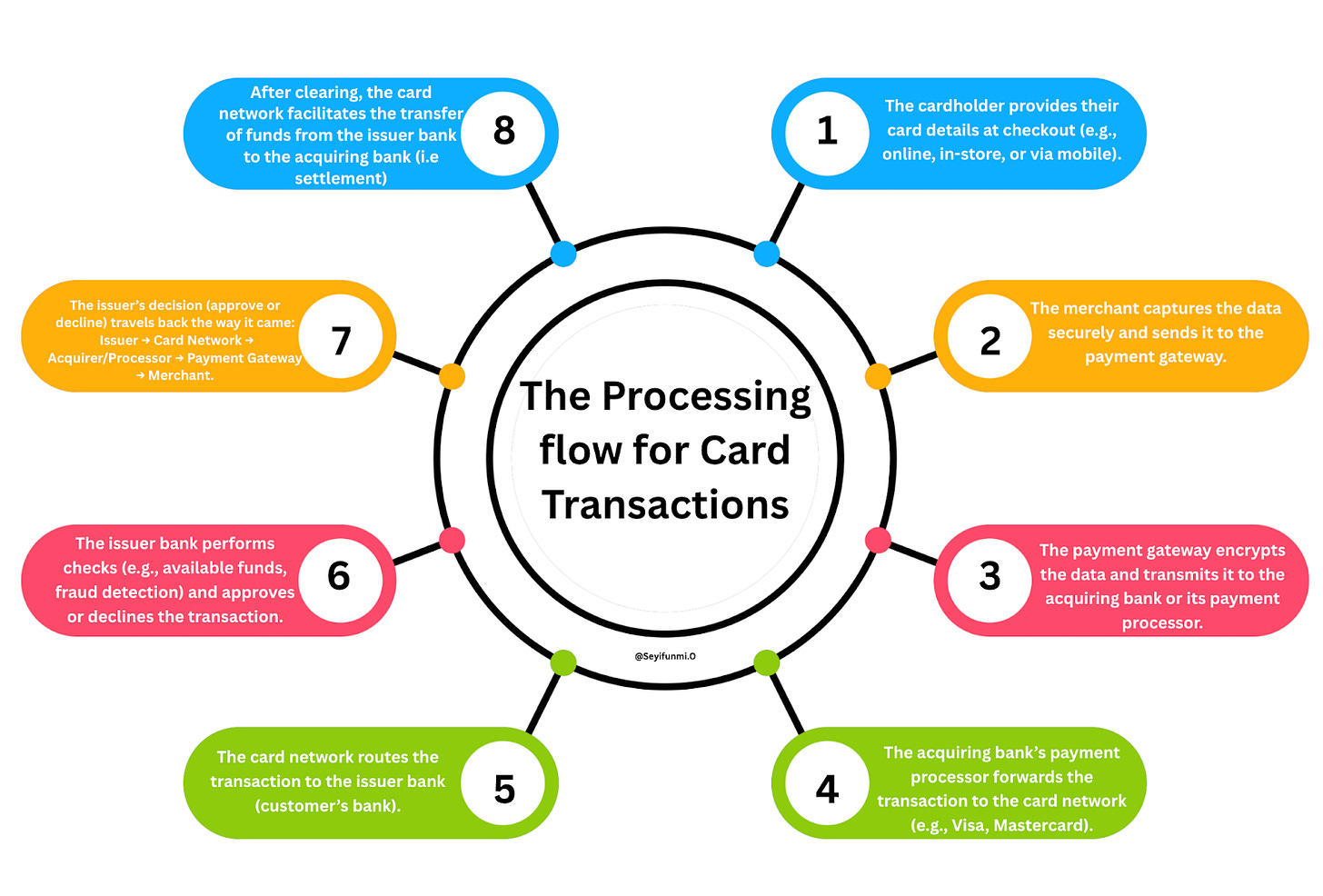

The Processing flow for Card Transactions

Now that you know the building blocks, let’s look at how they play out in practice:

1. Cardholder Provides Card Details

The transaction starts with the cardholder. They present their card details at checkout either by inserting or tapping the card at a POS terminal or entering the details (card number, expiry, CVV) online or via a mobile app. This step is the initiation of the payment request.

2. Merchant Captures and Forwards the Data

The merchant’s system (POS terminal or e-commerce checkout) captures the card details securely. For security reasons, merchants are not allowed to store sensitive details themselves. Instead, this information is packaged and sent to the payment gateway.

3. Payment Gateway Encrypts and Routes the Data

The payment gateway encrypts the transaction details to protect them from fraud or interception. It then transmits the information either directly to the acquiring bank or through a payment processor that specialises in formatting and routing the data to the correct network. This ensures sensitive cardholder information travels safely through the system.

4. Acquirer Forwards the Transaction to the Card Network

The acquiring bank (merchant’s bank) or its payment processor takes the encrypted request and passes it to the relevant card network. At this stage, the acquirer is essentially saying to the network: “Here’s a purchase request from our merchant, please check with the cardholder’s bank if payment can be made.”

5. Card Network Routes to Issuer Bank

The card network acts as the global switchboard. It identifies the card type and routes the request to the issuer bank (the bank that issued the customer’s card). The network ensures the request is formatted correctly, applies its own rules (such as interchange fees), and guarantees interoperability across different banks and countries.

6. Issuer Bank Decision (Checks and Authorisation)

At the issuer bank, multiple checks are performed:

Funds/credit check – Does the customer have enough money or available credit?

Fraud screening – Is the transaction suspicious (wrong CVV, unusual location, exceeded spending limit)?

Card validity – Is the card still active, not expired, and not blocked?

Based on these checks, the issuer either approves the transaction (reserving the funds for the merchant) or declines it (with a reason code, such as “insufficient funds” or “suspected fraud”).

7. Response Sent Back Through the Chain

The issuer’s decision (approve or decline) travels back the way it came:

Issuer → Card Network → Acquirer/Processor → Payment Gateway → Merchant.

At the merchant’s checkout, the customer sees an immediate response: “Approved” if the issuer agrees to pay, or “Declined” if not.

8. Clearing and Settlement (Money Movement)

While the authorisation happens instantly, the actual money transfer occurs later:

Clearing: At the end of the business day, the merchant’s bank and the cardholder’s bank exchange transaction records, ensuring everyone agrees on amounts and obligations.

Settlement: The issuer bank sends the money through the card network to the acquirer bank. The acquirer then deposits funds into the merchant’s account(, usually within hours to days depending on the type of transaction, after deducting applicable fees.

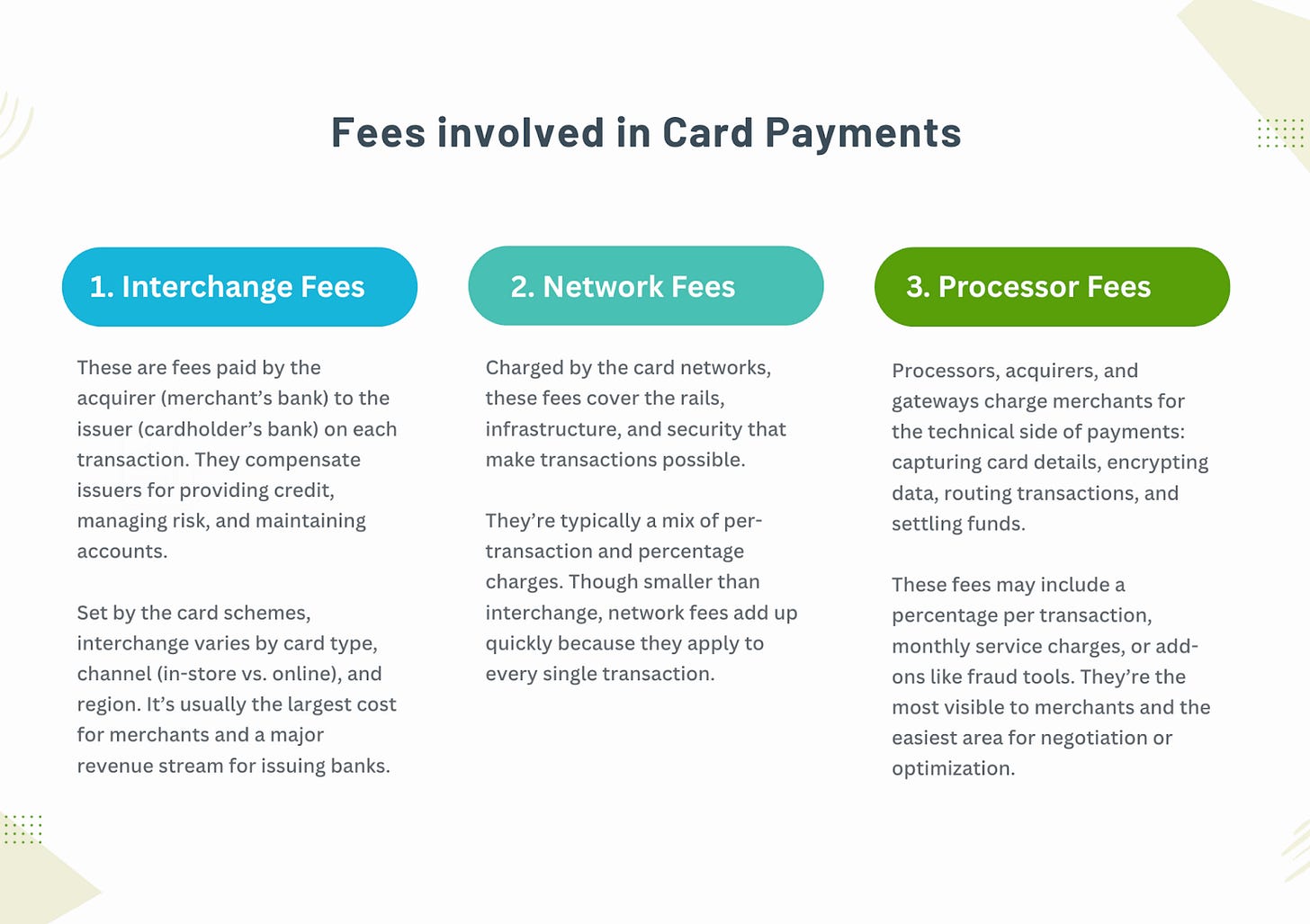

Speaking of Fees, these are fees involved in Card Payments

Factors to Consider Before Issuing Cards to Customers as a Product Offering

Issuing cards to your customers sounds like a natural extension for fintechs and digital banks but isn’t just about slapping your logo on a piece of plastic. It means entering the world of banking regulations, compliance, and ongoing financial risk. Requiring strong partnerships, compliance expertise, and thoughtful execution.

Here are some critical factors product managers must weigh before making the leap:

Customer Needs & Market Fit: Do your users actually prefer paying with cards, or do they lean toward wallets, bank transfers, or mobile money? Launching without this clarity risks building a feature that doesn’t truly serve them.

Regulatory & Compliance Requirements: Issuing cards automatically places you under strict financial regulations. You’ll need licensing (or a licensed partner), adherence to KYC/AML rules, and ongoing audits. Without this, your product risks being shut down before it starts.

BIN Sponsorship & Scheme Partnerships: You can’t issue cards without access to card schemes (Visa, Mastercard, Verve, etc.). This usually requires a BIN sponsor, that is a bank or licensed institution that gives you access to the schemes’ “rails.” Choosing the right partner determines how flexible, fast, and cost-effective your issuing program will be.

Technology & Infrastructure: From card manufacturing and personalisation to virtual card provisioning and API integrations, the technology stack must be reliable and secure. You’ll also need fraud detection systems, tokenisation support and smooth settlement processes.

Economics & Revenue Model: Card issuing comes with costs; scheme fees, BIN sponsorship charges, fraud losses but also revenue opportunities. Product managers must work with the necessary stakeholders to model the unit economics carefully.

Customer Experience & Card Lifecycle Management

A card isn’t just issued once, it must be supported throughout its lifecycle. That includes activation, PIN setup, lost/stolen replacements, renewals, and even dispute handling. Smooth experiences must be created for every stage of the lifecycle, not just the “new card” moment.

Cards began as a simple fix to a very human problem: people wanted a safer, more convenient way to pay without carrying bundles of cash or waiting on cheques. That small innovation, the Diners Club charge card, reshaped commerce, unlocked new business models, and gave rise to the vast global networks we rely on till now.

The lesson is simple; cards still matter because they solved yesterday’s problems, and they’ll keep evolving to solve tomorrow’s. As a Builder or Product Manager, your job is to understand that evolution and build with it in mind, not around it.

Until next week